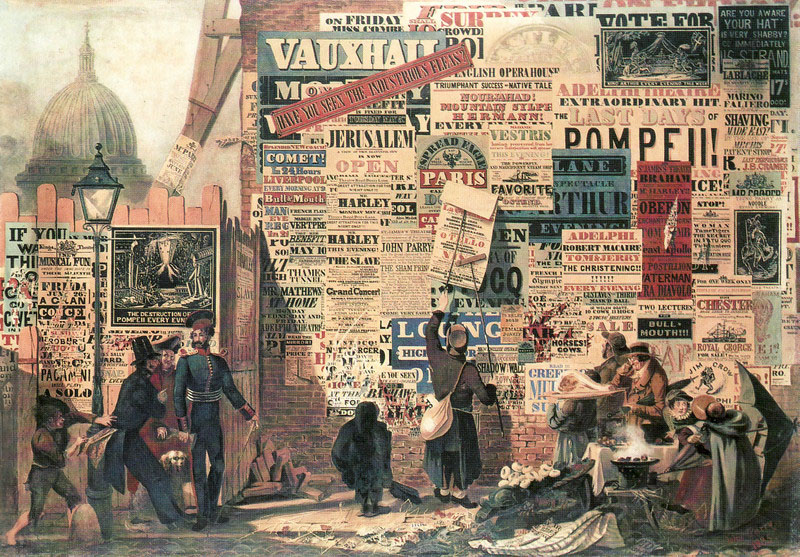

Mad Men is a popular TV series depicting 1960s advertising in America, the industry’s “golden age”. In one memorable scene, several creatives meditate about how to sell lipstick to women. Eventually they ask the chief creative’s PA what women might like. If they went on to discuss where to place the ad to maximise ROI, it was not depicted.

A ‘planner’ was a role invented by ad agencies such as JW Thompson so that they might understand their audiences a bit better. Now, sophisticated tools understand audiences which make data the world’s most valuable resource.[1] They have changed the industry fundamentally.

BUYING AND SELLING

Old school buying and selling of advertising space was a labour-intensive affair. ‘Programmatic advertising’ refers to the automation of this process. “Demand-side platforms” (DSPs),[2] “supply-side platforms” (SSPs), and “ad exchanges” are the jargon terms; these are simply pieces of software designed to optimise the price for buyers, sellers, and the brokers of ad space respectively. They interact to determine which ad gets placed where and for what price.[3] (These terms are particularly relevant for mobile advertising; and mobile browsing is becoming increasingly important).[4]

DSPs tend to be licensed as software as a service. Many people have experience using Adwords; DSPs are similar except that they are vendor-neutral. A company buying ads logs in, sets budgets, sets a target market, and a bot can do the rest. There are also vendor-specific ad management platforms for large players like Google and Facebook.

INCREASED EFFICIENCY

Programmatic adds value firstly via the immediate availability of live analytics: hours of expensive research, done instantly and for free. It permits ‘real time bidding’[5] which is what it sounds like; adverts can be purchased immediately. Instant feedback means rapid improvement, and clearly-visible ROI.

Transparent, navigable analytics, in programmatic but also new fields such as search engine optimisation, have encouraged DIY advertising approaches; many brands write text-based ads supplemented by some cheap design work and iterate improvements in-house. Digital agencies are now common; and they require different competencies to the old-style creative agencies, which face a sudden and unprecedented need to be justified. “The digital disruption is a fundamental one,” Sir Martin Sorrell, the CEO of WPP, said in an interview.[6]

INCREASED EFFECTIVENESS

The second way programmatic adds value is personalisation. ‘Half my advertising budget is wasted’ goes the adage, and by Jove, we might just figure out which half.

The technical stuff: in programmatic, the DSP is fed data about what to bid for by a ‘data management platform’, (DMP), which is the ‘data’ part of the data-led advertising model. (In some instances, DSPs have built-in DMPs).[7]

The data a DMP uses might be solicited from the buyer or the vendor of the ad space (i.e. a publisher); or it might be data which is bought from third parties; it might be taken from ‘ad tracking pixels’ which are tools to determine when a conversion has been made, and to map customer journeys.[8] It might be collected via ‘tags’ which can identify categories such as ‘IP address, Web browser, referral data’, ‘page views, searches, purchases,’ and ‘demographics and psychographics,’ in the case of Adobe software and many others. [8b]

It then groups the data into “audiences” (some extra applications can stitch diffuse identities together, and can serve you ads on your phone based on your desktop browsing) and importantly, it can ‘sync’ cookies. This is where it finds people viewing the same things as you and identifies them as a target based on their perceived similarity.[9] Then it sends instructions to the DSP, which puts a higher bidding value on the advertising space that person views. If you view a page, theoretically, somebody who matches your web habits might see an ad for a similar page. More noticeably, if you view a page, an advert from the page will follow you around until you clear your cookie cache.

BUT WHAT ABOUT

General Data Protection Regulation? Yes. GDPR will be something of a landmine under all this. Because of liability for data controllers, and data processors, companies looking to buy or sell ad space both need to be extremely vigilant when dealing with programmatic ad SaaS, much of which has been programmed to automatically import or export third-party data. This is an area in which ad space buyers and publishers are likely to violate GDPR, often without realising.

Programmatic advertising will take a hit even before GDPR arrives. In September 2017 Safari iOS 11 will introduce ‘intelligent tracking prevention’ which will change the way cookies work. For 24 hours cookies can be used for retargeting; if you look for product X, vendors of product X, Y, and Z, may retarget you for exactly 24 hours afterwards. Then, for a further 30 days, a website can remember your password using a cookie. If you don’t revisit within those 30 days, you are logged out and gone from memory forever.

For GDPR, in the digital marketing magazine ‘ad exchanger’, the chairman of a digital communications agency said, ‘I cannot see how programmatic can ever be GDPR-compliant unless it is limited to a small number of organizations, rather like a prospect pool.’[10]

The data rights of the subject seem to be causing the biggest furore. The system is too complex and diffuse. If an advertiser is asked to forget some data, and they’re using a demand-side platform connected to a data exchange, whom does the agency contact?

A second technical and legal challenge is at what point data ceases to be personal. If a publisher asks to track a user's smartphone location, which is explicitly flagged as sensitive personal data under GDPR; anonymises it; and it then sorts them into a category like ‘London’; aggregates that information with other users’ to derive a statistic like, ‘66% of our readers are based in London,’ which it puts alongside a similar set of audience statistics; and shares with third party potential advertisers without asking consent, this is probably not illegal because marketing is a legitimate purpose and the data is no longer ‘personal’.[11] (More guidance can be found on the Information Commissioner’s Office website).[12] But this model would still require restructuring because it would move all of the data analysis from the advertiser to the publisher, which are the party best placed to solicit personal information from the viewer.

On the advertiser side, plenty of information is still legal to collect. But mapped audience journeys, mapped conversion rates, and the websites they have navigated from, will be difficult without tracing single IP addresses. Crucially, the cookie operation is likely to become illegal. Cookie identifiers are personal data.

From recital 30: ‘Natural persons may be associated with online identifiers provided by their devices, such as internet protocol addresses, cookie identifiers, or other identifiers such as radio frequency identification tags. This may leave traces which, in particular when combined with unique identifiers and other information received by the servers, may be used to create profiles of the natural persons and identify them.’[13]

This means advertisers must explicitly ask permission for their use for targeted marketing. They may say, ‘no.’ Advertisers will therefore find it difficult to stitch together lots of demographic attributes about user X, even if they subsequently encrypted the data, because the aggregation of those attributes as being a single user would happen before the data had been encrypted.

If I wanted to target High Net Worth Londoners who were 23-30 and had an interest in fashion, it would be extremely difficult to do so. I would be unable to stitch a single user's’ behaviours together into a profile of this kind without some kind of cookie aggregation. This means programmatic advertising's restriction will cost publishers. Viewers’ attention simply isn’t as valuable if buyers cannot see things such as their age profile, likely salary bracket, and more.

Of course, there are two or three publishers which are so monstrously good at soliciting information from their users that they can persuade users to voluntarily enter things like where they work, their previous jobs, their age, what they ‘like’. It happens that the websites that can do this are massive, and would have a category as niche as 23-30 year old HNW Londoners in numbers big enough to spend an entire ad budget on; I would not have to find individuals from this group across multiple websites.

ZUCK YOU

The real winners out of this may be companies with superb information-soliciting models, that is, Google, Facebook, and soon Amazon; the very companies whose overreach the law was designed to fight. This may give them more of a monopoly over targeted marketing of this kind. Not only do they have impressive legal teams to demonstrate compliance, but they can do all of the aggregation and encryption in-house, so that the ad categories are only perused by third party ad buyers after it ceases to be personal data. There’s no need for stitching and hobbling together personal data from all over; they have all the data there and then.

Social ad buying APIs have had teething problems – e.g. bots triggering ‘clicks’ leading to ‘fraudulent’ high costs[14] (really, the savings on labour make the process cheaper). Or the accidental sale of unregulated ads to unpalatable parties; this is one thread of the Russia/US election interference scandal.[15]

A recent such scandal is that Facebook’s machine learning algorithm, which was tasked with innovating new categories of ad targets grouped by ‘likes’ recently suggested the category ‘Jew Haters’ as a potential target.[16] These were individuals grouped by activity on unsavoury pages. But this is more to do with a failure of their measures against hate speech than the inability of their algorithm to find groups with things in common; it is no surprise that a bot did not have the common sense to see that such a grouping was inappropriate. (Facebook has also allegedly attempted to target ‘teens who feel worthless,’ although they dispute this.)[17]

It feels that the teething problems are just that – teething problems – and the level of potential personalisation in the advertisements they rend is extremely impressive. Advertising’s big boy is going to get bigger.

THE PAST AND THE FUTURE

Publishers use what they know about their audiences to maximise their ad space value. In the wake of GDPR, the ad publishers that can legally solicit large amounts of information from lots of people whom it can put into anonymous but specific categories of ad viewer with specific attributes, will be empowered in the marketplace.

YouTube has access to your demographic details and what videos you view (YouTube content producers have access to neat audience analytics pages which helps lubricate deals with sponsors); Facebook has access to a huge suite of likes, hobbies, and interests (Cambridge Analytica, whose targeting abilities are renowned, use Facebook data); perhaps most usefully, Google knows what you’re searching for in the immediate term. ‘Click-through-rates’ (CTRs) from the text-based, softly naturalised ads at the top of Google searches tend to be much higher than the CTR on a random ad, even which use demographic targeting data. CTR might not be the best measure, but it is a measurable measure.

Old school Mad Men types at creative agencies sometimes argue that while digital analytics measure whether people follow a digital trapdoor to your website, they do not measure whether you have become a ‘brand’ in a real sense. This argument has not stopped an enthusiastic shift away from them.

Advertising in the UK is an expensive business; well-paid executives operate fashionable agencies with large London offices. It attracts creative talent, and involves awards for creativity such as Cannes Lions, D&AD pencils, and Drum Marketing Awards. There is prestige, and there is hierarchy. Much of this is unsustainable in the wake of Facebook with DIY/API advertising approaches. There are no ‘mad men’ now: people talk soberly and at length about ROI, and profits are falling anyway. The gut punch to profit the advertising industry is now facing has already happened to online publishers.

To take a severe example, WPP, the UK’s largest agency, issued a series of warnings as its pre-tax profits had dropped 52.4% since the previous year in August 2017.[18] Parts of WPP were restructured in September 2017.[19]

As if to confirm their worries about the trend towards an uncompromising focus on data-driven ROI, in late 2016, Karmarama, a well-known creative agency, was bought by Accenture.[20] Worried about a robot taking your job? Advertisers sometimes worry their forerunners are management consultants.

For the time being, targeted adverts can still feel crude. The industry has made some progress from asking the nearest woman what women might like in a lipstick ad – and not thinking at all about where to put it. But the zealous collection of highly specific data does not equal correspondingly effective creative. The mechanics of desire is something that data has not yet cracked.

[1] The Economist, 2017. ‘The World’s Most Valuable Resource is No Longer Oil, but Data.’ [Online.] Available: https://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21721656-data-economy-demands-new-approach-antitrust-rules-worlds-most-valuable-resource [Accessed 20/09/2017].

[2] Marshal, J., 2014. ‘WTF is a demand-side platform.’ Digiday. [Online.] https://digiday.com/media/wtf-demand-side-platform /[Accessed 20/09/2017]

[3] This article is simplifying. There are alternatives to SSPs, such as ‘ad mediators’, and you may be more familiar with older ‘ad networks’ than the ad exchange and DSP combination listed above; however, these are becoming indistinct. Many ad networks now offer the kind of intuitive user interface and tracking tools that DSPs do, and ad exchanges do interact with ad networks.

[4] Titcomb, J. 2016. ‘Mobile web usage overtakes desktop for the first time.’ Telegraph. [Online.] Available: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/2016/11/01/mobile-web-usage-overtakes-desktop-for-first-time/ [Accessed 20/09/2017]

[5] Marshall, J., ‘WTF is real time bidding.’ Digiday. [Online]. Available: https://digiday.com/media/what-is-real-time-bidding/ [Accessed: 20/09/2017]

[6] Financial Times. 2017. ‘Sharp drop in consumer ads sends WPP shares plunging’ [Online.] Available: https://www.ft.com/content/2e06a7e2-87cb-11e7-bf50-e1c239b4578

[7] Marshall, J. ‘WTF is a digital management platform.’ Digiday. [Online]. Available: https://digiday.com/media/what-is-a-dmp-data-management-platform/ [Accessed 20/09/2017]

[8] Facebook. ‘How does the conversion pixel track conversions.’ [Online]. Available: https://www.facebook.com/business/help/460491677335370 [Accessed 20/09/2017]

[9] Kihn, M., 2017. ‘How Does a DMP Really Work?’ Gartner. [Online]. Available: http://blogs.gartner.com/martin-kihn/how-does-a-dmp-really-work/ [Accessed 20/09/2017]

[10] Roy, M., 2017. ‘GDPR: the Death Knell for Programmatic Advertising?’ Ad Exchanger. [Online]. Available: https://adexchanger.com/data-driven-thinking/gdpr-death-knell-programmatic-advertising/ [Accessed: 20/09/2017]

[11] General Data Protection Regulation, 2018. Article 4. Available: https://gdpr-info.eu/art-4-gdpr/

[12] ICO, 2017. ‘Direct Marketing.’ [Online]. Avialable: https://ico.org.uk/media/for-organisations/documents/1555/direct-marketing-guidance.pdf [Accessed 20/09/2016]

[13] General Data Protection Regulation, 2018. Recital 30. Available: https://gdpr-info.eu/recitals/no-30/

[14] Gallagher, K., 2017. ‘Ad fraud estimates doubled.’ [Online]. Available: http://uk.businessinsider.com/ad-fraud-estimates-doubled-2017-3 [Accessed 20/09/2017]

[15] Hatmaker, T., 2017. ‘Facebook sold more than $100,000 in political ads to a Russian company during the 2016 election’ TechCrunch. [Online]. Availabile: https://techcrunch.com/2017/09/06/facebook-russia-ads-election/ [Accessed 20/09/2017]

[16]Angwin,J., Varner, M., and Tobin, J., ‘Facebook Enabled Advertisers to Reach ‘Jew Haters.’’ ProPublica. [Online.] Available: https://www.propublica.org/article/facebook-enabled-advertisers-to-reach-jew-haters [Accessed 20/09/2017]

[17] Machkovech, S., 2017. ‘Report: Facebook helped advertisers target teens who feel “worthless” [Updated]’ Arts Technica. [Online]. Available: https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2017/05/facebook-helped-advertisers-target-teens-who-feel-worthless/ [Accessed 20/09/2017]

[18] Financial Times. 2017. ‘Sharp drop in consumer ads sends WPP shares plunging’ [Online.] Available: https://www.ft.com/content/2e06a7e2-87cb-11e7-bf50-e1c239b4578

[19] Oster, E., ‘WPP Is Merging 5 Consultancies and Design Agencies to Form a New Global Offering.’ Adweek. [Online]. Available: http://www.adweek.com/agencies/wpp-is-merging-5-consultancies-and-design-agencies-to-form-a-new-global-brand-offering/

[20] Spanier, G., ‘Accenture ‘is building a new breed of agency’ with Karmarama.’ Campaign. [Online]. Available: http://www.campaignlive.co.uk/article/accenture-is-building-new-breed-agency-karmarama/1417049

Leave a Comment